XXXII and XXXIII Pozzuoli (Puteoli)

What3words – i. rider.havens.taking ii. scores.goad.self

Construction - i. 200AD ii. 100BC

Capacity - i. 40 - 60,000 ii. 25,000

Visited January 2025

Status – Flavian Amphitheatre is a must visit. The older one is inaccessible. Source of early ‘souvenir’ glassware? Read on.

When you first visit Pozzuoli there is a definite smell in the air. Not badly maintained Mediterranean drains, but volcanic sulphur. ‘Solfatara di Pozzuoli’, a dormant, but not quite extinct volcanic crater east of the town centre, provides the distinctive fragrance when the wind is blowing the right way. Earthquakes are frequent. From August 1982 to December 1984 there were hundreds of tremors which peaked on 4 October 1983 damaging 8,000 buildings and raising the sea bottom in the bay by 2m. As a result, cruise ships and other large vessels can no longer use the port. An earlier consequence of the associated earth movements affected the Roman coastal resort of Baiae at the western end of the bay. Written of as the Las Vegas of ancient Rome, it contained villas owned by Emperors including Julius Ceasar, Nero, Hadrian and Claudius, and elaborate bath complexes fed and heated by underground volcanic springs. By the 4th century AD the lower part of the town had begun to sink below the bay and was completely submerged by the 8th century. Underwater archaeology has revealed and preserved extensive remains, walls, statues and mosaic and marble floors which can now be visited by divers. If you look at the bay on satellite maps and zoom in just offshore, you can see the submerged buildings and streets beneath the shallow water.

From its colonisation by Rome in 195BC until Emperor Claudius started the development of Ostia and Portus at the mouth of the Tiber in 42AD, the Roman port of Puteoli, grew to the west of the site of a Greek colony on which now sits the centre of Naples. It served and thrived as the largest imperial port of the expanding empire. It harboured grain ships from Alexandria, and produce was transported the 170 miles to the capital via the super highways of the Via Domitiana and the Via Appia. Pozzuoli has two amphitheatres. The larger, later and much better preserved example reflected technical progress in amphitheatre design together with the growing population and importance of the city.

The Flavian Amphitheatre

The republican ‘small’ amphitheatre with a capacity of 25,000 was supplanted by a new structure with seating for in excess of 40,000 during the reign of the Flavian Emperors. The ‘Flavian Amphitheatre’ (confusingly this is also the name given to the Colosseum) is officially the third largest of the Roman empire. When completed it was elaborately decorated and had a network of underground vaulted passages and rooms accommodating lifts, cages and scenery docks, to serve the spectacles which took place above.

A marble plaque found on the site states its construction was financed by the (prosperous) city, rather than through the gift of a wealthy benefactor, politician or family. The outer walls and most of the marble were long ago stripped and quarried for church building etc. but much of the cavea remains, together with the very well preserved vaults below. These were constructed of red brick with arched vaults above, using concrete based on the local volcanic dust. The vaults contain many sections of corinthian columns, discovered when it was excavated. These are assumed to have been dumped there, together with many tons of rubbish and spoil, in order to enable the sheltered area above to be used for horticulture in the post-roman centuries.

The amphitheatre is surrounded by high railings and the entrance is at the western end. When I visited on a Monday in January 2025 the site was closed to the public for out-of-season works to stabilise earthquake damage, and the western entrance was scaffolded. A friendly site guide however let me in, and showed me around the vaults. He suggested more of the site might be open on the Thursday and I duly returned in the morning on the way to the Airport, paid my €5 and was admitted to the arena. A short video clip above scans around it.

The ‘Small’ or Republican Amphitheatre

What’s left of the older amphitheatre is a matter of metres away from the larger structure on the east side of the Via Solfatara. It is very hard to see any of the remains from public viewpoints, and aerial photographs suggest that it is largely covered by the gardens of properties which surround it. Its ground level is elevated probably 8-10m above the surrounding streets, level with that of the main Rome-Naples railway which crosses the Via Solfatara on a bridge. Construction of the railway destroyed the entire northern half of the amphitheatre remains. There are said to be a number of arches of the external walls remaining. To see any of it without getting through the locked gates of private apartment buildings, gardens or rooftops (believe me, I tried), you can go through a pair of gates opposite the eastern end of the main amphitheatre (flanked by stone gateposts sporting eagles? with wings spread) and turn left behind the apartment building into a courtyard. This is truncated by a high wall containing a bricked-up Roman arch. You can also catch a glimpse by entering the Pozzuoli Solfatara railway station and walking to the very end of Platform 1. From there you are then sufficiently high up to be able to glimpse the external wall amid the dense foliage which covers the remains of the structure on the opposite side of the tracks.

Less manic and crowded than Naples. A good base for wider exploration, and apparently the town where Sofia Loren grew up.

The Glass Bottles

A seracg following up on a reference to the existence of a ‘glass vase depicting the city with both amphitheatres’ has led to bottles which were discovered in several parts of the empire and subsequently ‘collected’ in the modern era. Of about thirteen complete or broken examples, some of the best ended up in Prague, St.Helens England, Corning USA and Portugal. The Corning example, found in Tuscany, is pictured at the head of this page.

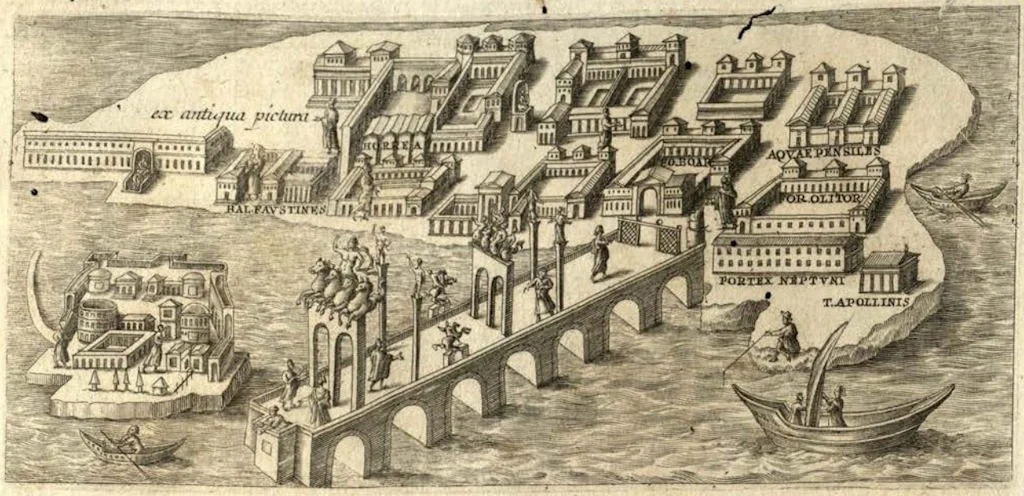

These globular glass bottles with long necks display incised graphic representations of Puteoli, its harbour and various temples and public buildings. There is nothing similar known relating to any other city or part of the empire. When the graphics are transcribed and flattened out, it is clear that they are related versions of the same design. Each shows an arched harbour breakwater on top of which there are two decorative gates, one topped by seahorses and one by mermen, together with single ‘pilae’ columns supporting statues. In the town itself the vases depict various public buildings, a temple with a seated statue of a god, a semi-circular ‘greek’ style theatre, a marked amphitheatre and another arena. On the St. Helens example (At the Pilkington Museum of Glass) and the one found in Merida Spain, there appear to be two amphitheatres, however in the Prague and Portuguese examples the upper structure is elongated and flat at one end. It is clearly marked ‘stadivm’ or ‘stadiv’ on all but the Portuguese example. Above Puteoli are the remains of a stadio hippodrome or horse/chariot racing circus. My conclusion is that depiction of the upper arena to resemble an amphitheatre is more likely to be a drawing error rather than evidence of simultaneous use of the two Puteoli amphitheatres.

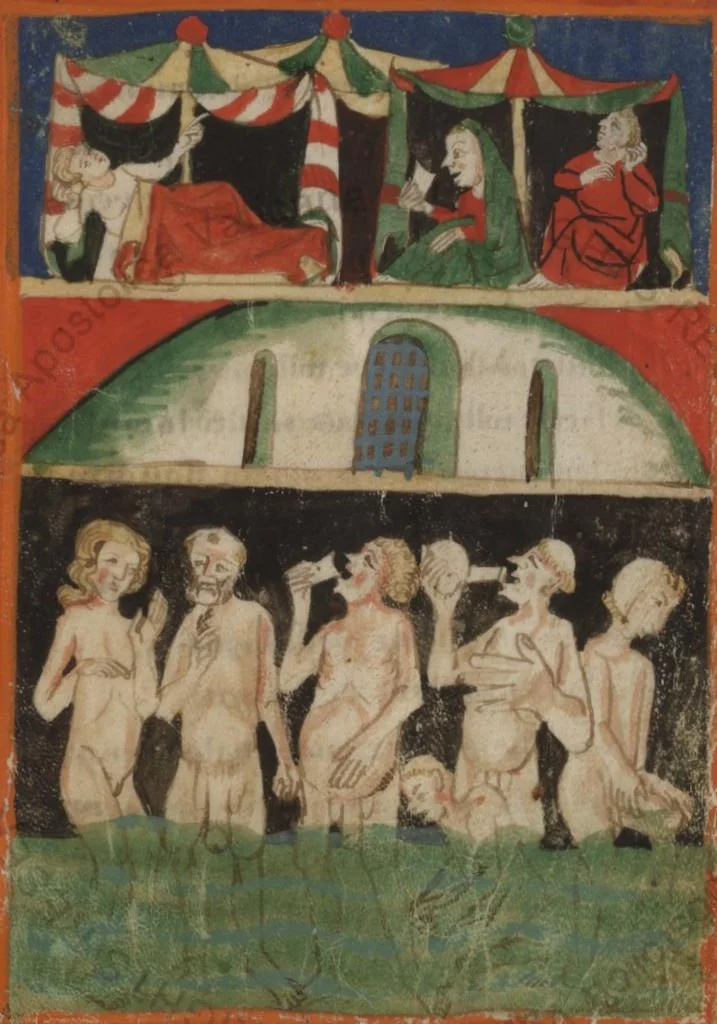

As to the function of the bottles, there is a clue in a medieval painting - an illustration in a manuscript of De balneis Puteolanis (The baths of Puteoli) by Peter of Eboli, from the early 13th century. It shows a bathing man drinking from a bottle that has the same shape as the Roman examples. It is possible that patrons of the sulphurous bath complexes of Puteoli and Baiae not only drank health-giving spa waters from these elaborate glass flasks, but also took full examples home. Graphics of the decorations on the Puteoli vases are included in the gallery section below.

The Flavian Amphitheatre is to the left behind railings. The smaller amphitheatre sits to the right of the railway bridge in the distance.

16th Century engraving by Bellori from a lost Roman wall painting. It depicts a stylised view of Puteoli/Baiae featuring the massive arched breakwater, pilae, arches topped by seahorses and mermen, an amphitheatre, temples and villas, all of which feature on the glass vases.

Graphic of Merida Bottle. This version includes a ship at anchor in the harbour.

Graphic of Prague Bottle

Graphic of Portugal Bottle

Graphic of St Helens Bottle

13th century depiction of the baths of Puteoli featuring drinking flask. (and an impressive selection of medieval todgers)

17th Century view showing remains of Roman Breakwater

Arch of the 'Small' Amphitheatre

The 'Small' Amphitheatre from Railway Platform

Map of Puteoli bay area showing locations of Stadio, Amphitheatre, breakwater and underwater remains of Baiae